I have quoted text from the 2012 Thomas and Mercer edition of Live and Let Die. Original manuscript published in 1952. Page numbers have been accordingly provided for reference. I lay no claim to any quote. Ian Fleming Publications Ltd currently owns all the rights to the James Bond novels.

There are moments of great luxury in the life of a secret agent. There are assignments on which he is required to act the part of a very rich man; occasions when he takes refuge in good living to efface the memory of danger and the shadow of death; and times when, as was now the case, he is a guest in the territory of an allied Secret Service. p. 1

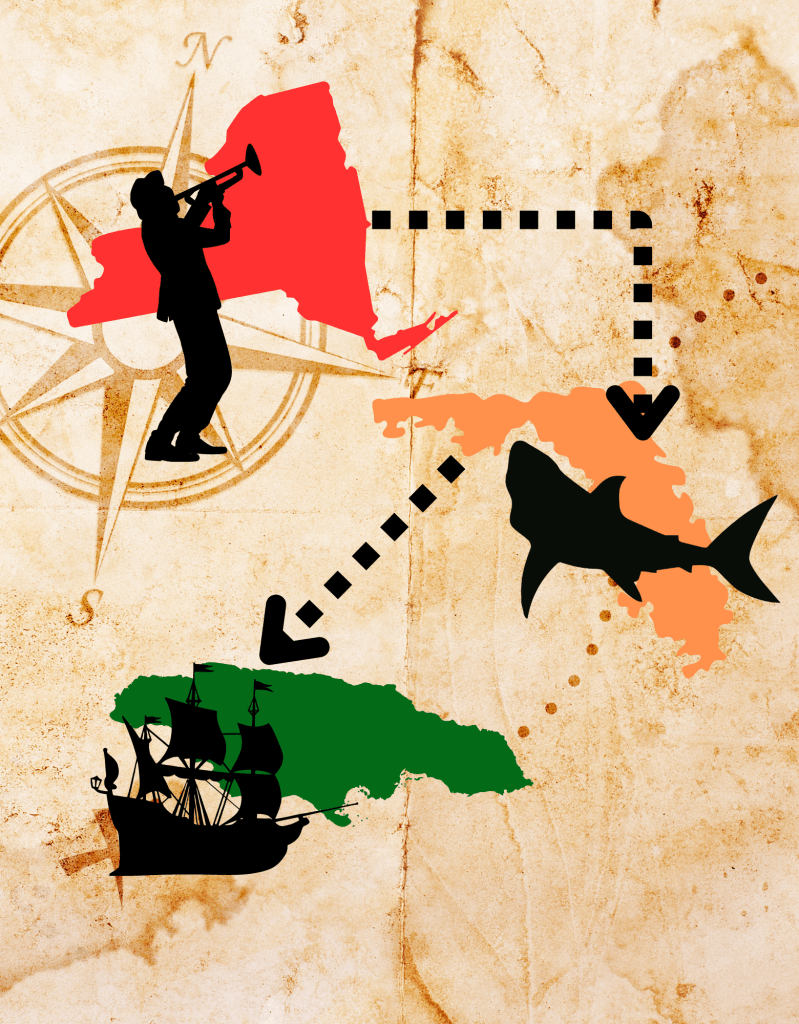

The second of Ian Fleming’s thrillers about James Bond is a slightly different pace from Casino Royale. This time, Bond is on the trail of a man known as Mr. Big, suspected of smuggling old pirate treasure into Harlem by way of St. Petersburg, Florida and turning it into cash for SMERSH and the USSR.

Live and Let Die has gained some notoriety in recent months mostly for its “outdated” language, something which I covered when discusses whether Ian Fleming’s works should be updated in the first place.

If the outdated racial terminology is all you focus on in the book, however, then you will miss several very important details that are in the book and give you a picture of the world only our grandparents and great-grandparents knew and experienced. As an elder millennial, I got to have a glimpse of them in my childhood, but Live and Let Die lets me see them again in astonishing detail.

American English had more distinctive dialects.

” ‘Sho have, Mister Bryce. Yassuh.” […] ‘Shouldn be telling’ yah this Mister Bryce, but here’s play of trouble ‘n this train trip. Yuh gotten yoself a henemy ‘n dis train […]. Ah hears ting which ah don’ lie at all.’ p. 97

Anyone who loves old Hollywood classics from the first half of the 20th century will no doubt be more familiar with the various dialects portrayed. Everything from Mid-Atlantic to the heavily accented Deep South mixed with New York dialect spoken in Harlem in Live and Let Die, American English had far more variety to it than we’re probably used to hearing these days.

If you grew up in the American South, especially in areas where African culture was more pronounced such as New Orleans or Charleston, then you may actually remember the dialect portrayed in Live and Let Die or a least bits of it. This is a time before R&B, Rap, and Ebonics became mainstream.

Now, Ian Fleming’s version of a “black” dialect was most likely derived from Eddie Anderson, a great comedian and long-time radio star. He starred in a few movies here and there too, mostly in a comedic capacity. We don’t always like to acknowledge this particular era of the entertainment industry because we have come to view such things as derogatory. But, it was a living and it wasn’t domestic work.

We shy away from this today, in fear of giving offense. This is understandable but it’s a terrible pity because it robs some of the variety that existed in the first half of the 20th century and which rapidly disappeared. Having it in the novel gives you a better appreciation that there was more to American than the proverbial white culture of the 1950s.

There aren’t the exaggerated Southern drawls we’re used to seeing in the movies, but something that’s more lively and somehow more real than the cookie-cutter portrayals we’re spoon-fed. Ian Fleming gives us something other than the Jim Crow South here, and something a little more real than housewives trying to one-up each other.

But then, that may be my own nostalgia kicking in. My grandparents were from Charleston and worked mostly with blacks. My grandmother was in the health department and got to experience a lot of Geechee and Gullah culture first-hand. My grandfather ran a construction business where, once again, the Geechee and Gullah dialects (and accents) were mostly used on the job site.

American cuisine before Julia Child.

‘The scrambled eggs’ll be cooked with milk,’ said Bond. ‘but one can’t eat boiled eggs in America. They look so disgusting without their shells, mixed up in a tea cup the way they do them where. God knows where they learned the trick. From German, I supposed. And bad American coffee’s the worst in the world, worse even than in England.’ p. 111

What Bond is referring to in the quote, is an actual thing. Milk is supposed to add a richer flavor, but if you have really fresh (and free-range) eggs and beat them well until they’re fluffy with a good dollop of butter in the pan, the milk is unnecessary. Boiled eggs in America are usually “hard boiled” meaning the yolk is completely firm. The same thing in England would have been until the white is firm and yoke just set.

His lunch at the Regis St. James in New York was basically hamburger patties and French-cut potatoes (fries).

After the divine caviar and champagne of Casino Royale, this is quite a let-down. And a scathing review of American cuisine if ever there was one.

But then, I remembered Julia Child.

See, if you read Julia Child’s memoirs of her time in France, she’d never experienced anything nearing the Dover sole in France before. In fact, it was her time in France that changed her entire outlook on food because she saw what it could be.

One of the first things she had to learn, ironically, was how to properly cook eggs.

Even in later years, when she was still filming programs for PBS, she’ll refer to her childhood and what food was available then. The Ceasar salad, for instance, wasn’t American, it was an import from Tijuana. When she filmed her episodes with Emeril Lagasse or Nancy Silvertone, it was to an audience that didn’t always understand or realize the sheer variety of food in the United States.

Ma Frazier’s was a cheerful contrast to the bitter streets. They had an excellent meal of Little Neck Clams and Fried Chicken Maryland with bacon and sweet corn. p. 47

Food was simpler in the 1950s. There weren’t reduction sauces, fancy plating, or a variety of flavors for any but the most wealthy. “Soul food” and Southern cooking weren’t as common as a Cracker Barrel. It was stuck in tiny out the way places like Ma Frazier’s where Felix Leiter takes Bond to get a late night meal in Harlem.

In short, we’re looking at a very different food landscape in Live and Let Die. One that most people living today probably don’t even realize existed.

Florida before Orlando really was a bunch of retirees.

And, everywhere, a prattling camaraderie, a swapping of news and gossip, a making of folksy dates for the shuffleboard and bridge-table, a handy round of letters from children and grandchildren, a tut-tutting about prices in the shops and the motels. p. 126

When Bond arrives in St. Petersburg, his horror at all the retirees is somewhat comical. If a bit disrespectful to the elderly.

But even when I was a little girl, that is what Florida was known for. Nursing homes, oranges, and tourism for the beaches. There were citrus fruit stands, which have all but disappeared unfortunately, there were a few beauty spots like Silver Springs, Tarpon Springs, and Miami.

But Orlando didn’t exist yet. There was no Sea World, Universal, Busch Gardens, or Disney World. Families weren’t as common in Florida as vacationers and retirees. Even 30 years ago, finding a native-born Floridian was like finding a needle in a haystack. Everyone moved to Florida, but they were rarely born here.

And the type of hotel Bond and Leiter stayed at in St. Petersburg can still be seen in some spots in Florida although those are getting fewer and fewer as time goes on.

This isn’t a nostalgic detail, but it is a forgotten piece of history.

Before the war, at the end of an evening, one used to go to Harlem just as one goes to Montmartre in Paris. p. 38

Felix Leiter makes reference to “N–– Heaven” in the book. This is not, as you might first assume, being used as a racial slur. Leiter is actually referring to a novel by Carl Van Vechten, written in 1926 about Harlem during Prohibition. If you want to know more, read Kelefa Sanneh‘s article “White Mischief” in The New Yorker on Van Vechten.

Van Vechten’s book is highly controversial even now, although if you go through some of the reviews on GoodReads, it’s sometimes assigned reading in courses on the Harlem Renaissance. What makes it so intriguing, however, is that it had several references to Langston Hughes, possibly the best poet America ever produced.

In fact, Langston Hughes was both friends with, and a fan of, Van Vechten’s work.

With all the criticism for Bond that character, it’s almost appropriate that a polarizing novel is included in Fleming’s own work. Almost as if it’s a wink at the reader to say “there’s more to see here than what you perceive.”

Did Fleming know the furor over terminology and history that was to come almost 100 years after the Harlem Renaissance? Probably not. No more than Shakespeare could have predicted the Protectorate or Restoration. Classics, after all, are often made more important by the history that happens after they’re written.

Such is the case with most 20th century literature. Novelists like Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Harper Lee mostly get their status because of their connection to the history of the time in which they wrote. Not necessarily because they’re just that great at writing or telling a transcendent story.

I mention this because Fleming’s connection to 20th century history as far as Live and Let Die is concerned, is part of the reason why it’s such a good book in the first place. Just as Casino Royale is like watching Cary Grant and Grace Kelley dashing through the French Riviera in To Catch A Thief.

It’s the tiny details of a bygone era, like Sanka coffee on the train, or the differences between American and British men’s fashions that make it work, and make it work well. Beats the very unbelievable escape scene across the alligators that was in the movie!

Help support both the blog and my fiction writing!

Freelancing is what I do to pay the majority of my bills, but the blog is still a labor of love. If you like classic literature and creativity content, please consider supporting my blogging efforts by donating below.

Everything goes back into the blog somehow, whether that’s another round of books, more coffee, or maintaining the website.

And, as always, please like and refer others to the blog. All it takes for something to be preserved is one person at a time realizing that it’s worth saving.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

All money donated goes to keeping the posts coming and the website running! Whether that’s enough for a cup of coffee, or for another book to show you, every little bit helps!

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from K. B. Middleton, LLC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 thought on “Nostalgic Details in the Second Bond Book and a Piece of Forgotten History”